Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s music was too sophisticated for Hollywood and too tuneful for Europe. Alastair McKean discusses one of the great 20th century shouldabeens.

There’s a 1955 photograph of the actor Alan Badel having a conducting lesson, in preparation for his appearance as Richard Wagner in the film Magic Fire. Costumed in a flamboyant approximation of a 19th-century tailcoat, and manically grimacing, Badel resembles the great composer somewhat less than he does Dracula. Judging from the desperation with which he clutches the baton while staring hectically in the rough direction of the score, it’s clear that he’s destined to join that long list of actors who attempt to convince us they are musicians, and fail magnificently. To Badel’s left, serving as his model, is the genuine article: a gentleman holding the stick with a natural, unaffected power. This man is older, thinner. He has shrunk since his immaculately tailored suit was made, and he looks directly into the camera with a bleak weariness. Two years later he was dead. He was 60.

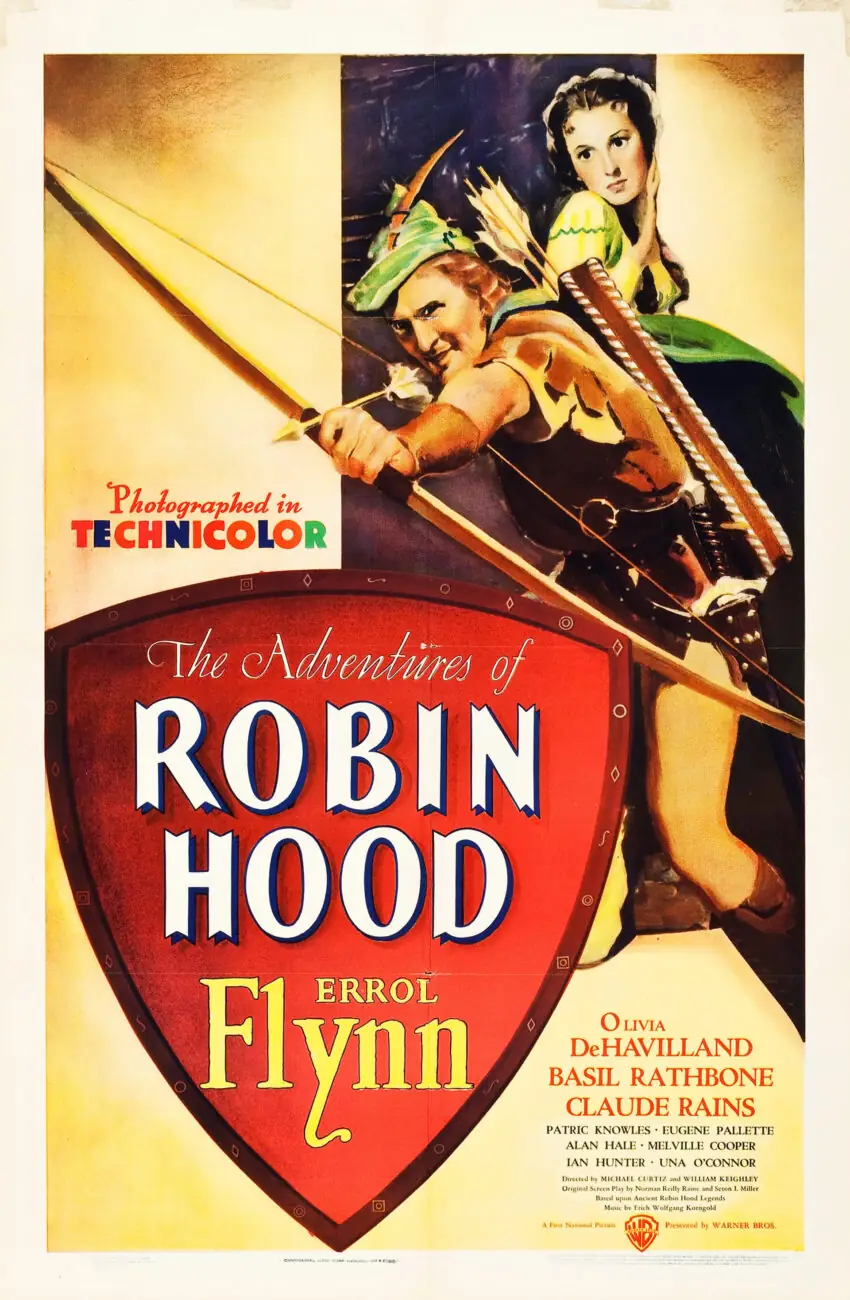

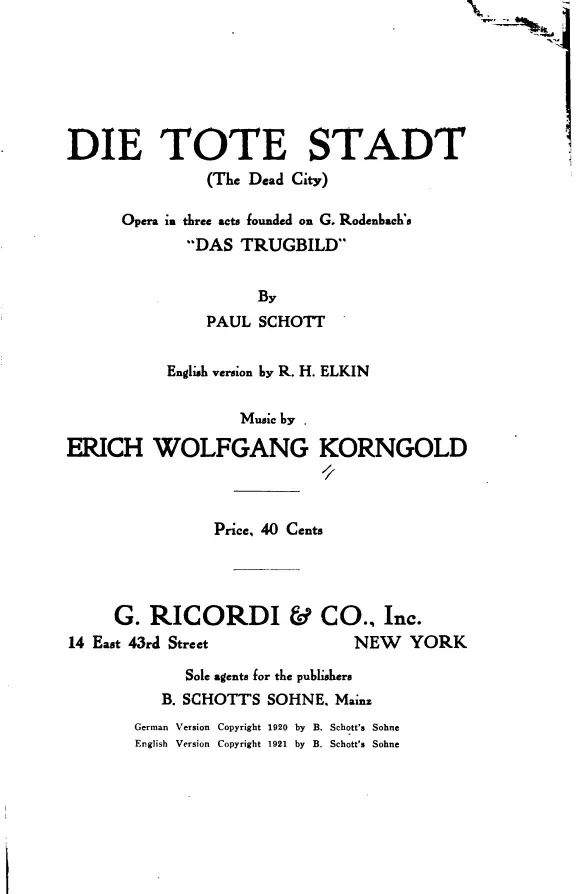

This was Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Not first and foremost a conductor (although he was a good one), he was a composer, and had been working in Hollywood since 1934. Magic Fire was the last of his 22 films. He composed for a wide range of movies, but was best known for his work on the Errol Flynn swashbucklers of the Golden Age. The greatest of these scores is for a 1940 pirates-and-treasure saga called The Sea Hawk. Nowadays the film is the preserve of nostalgia buffs, but if you do catch it on afternoon TV, you’ll miss a lot of the music; 1940s recording technology is what it is, and there are long action sequences where Korngold’s music can barely be heard over the din of battle. Such is the lot of a movie composer – but what a waste! This music is breathtakingly exciting, and in the concert hall, its energy and panache are irresistible.